At a Glance

- Jury began deliberations for Adrian Gonzales, first officer tried over the hesitant Uvalde police response that left 19 children and two teachers dead.

- Prosecutors say Gonzales abandoned his duty by failing to confront the gunman; defense warns a conviction could make police even more hesitant.

- Gonzales faces 29 counts of child abandonment or endangerment and up to two years in prison.

- Why it matters: The verdict will set precedent for whether officers can be criminally punished for inaction during mass shootings.

A jury started weighing the fate of Adrian Gonzales on Wednesday, the first police officer to stand trial for the delayed law-enforcement response to the 2022 Robb Elementary massacre in Uvalde, Texas. Prosecutors told jurors the case is about a simple failure to act while children were slaughtered inside a fourth-grade classroom.

Gonzales, a former Uvalde schools officer, is charged with 29 counts of child abandonment or endangerment tied to the 19 students killed and 10 wounded during the attack. He faces up to two years in prison if convicted.

Special prosecutor Bill Turner framed the case bluntly in closing statements: “This is a failure to act case.” He argued Gonzales had a duty to move forward even if it meant entering the building alone to face the gunman.

“We’re expected to act differently when talking about a child that can’t defend themselves,” Turner said. “If you have a duty to act, you can’t stand by while a child is in imminent danger.”

Defense: “The monster … is dead”

Defense attorney Jason Goss countered that Gonzales was not responsible for the massacre. “The monster that hurt those kids is dead,” Goss told jurors. “It is one of the worst things that ever happened.”

He warned that convicting Gonzales would tell police they must be “perfect” in crisis and could make officers more hesitant to respond at all.

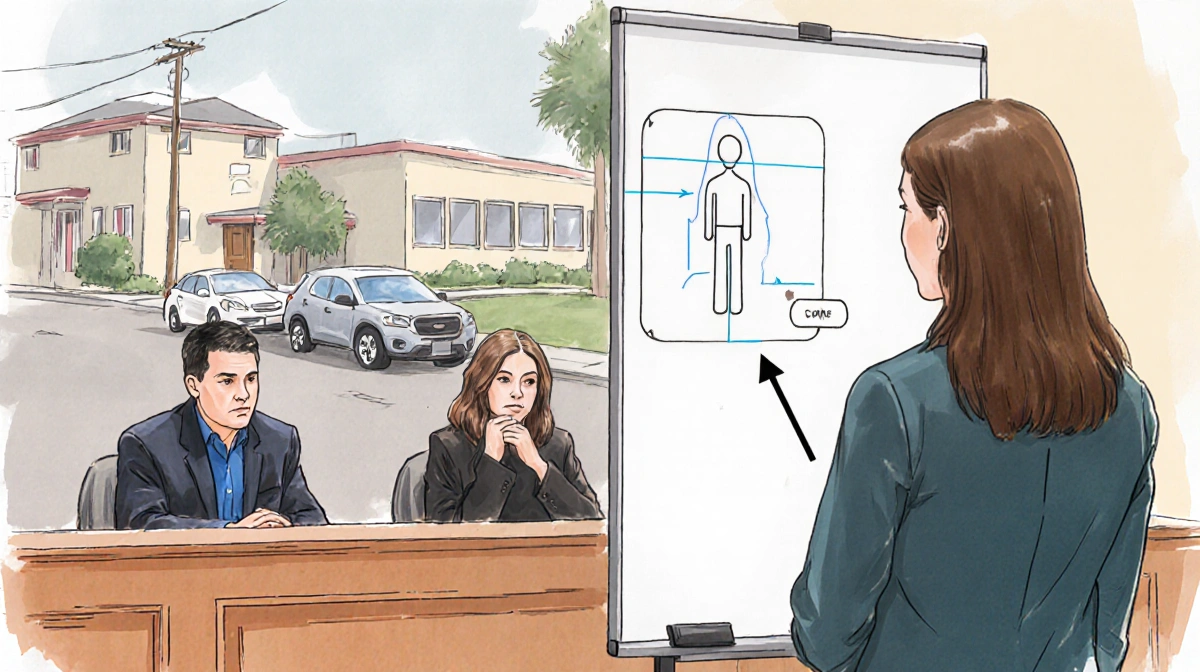

Gonzales, 52, did not testify. Body-camera footage shows he was among the first officers to enter a smoky hallway and try to reach the killer. His lawyers say he risked his life going into what they called a “hallway of death” while others held back.

Key evidence presented

- Prosecutors called 36 witnesses over nine days beginning January 5.

- Defense presented two witnesses, including a woman across the street who said she saw the shooter ducking between cars-supporting Gonzales’s claim he never saw the gunman.

- Graphic photos from inside the classrooms and emotional teacher testimony detailed the chaos.

Trial moved 200 miles

The case was moved from Uvalde to Corpus Christi after defense attorneys argued Gonzales could not receive a fair trial locally. Victims’ families still made the long drive to attend.

Early in the trial, the sister of slain teacher Irma Garcia was removed after an outburst following officer testimony.

Only two officers charged

Gonzales led an active-shooter training course two months before the attack, yet prosecutors say he abandoned that training and failed to stop Salvador Ramos before the 18-year-old entered the school.

Teacher Arnulfo Reyes, shot along with all 11 of his students, described seeing “a black shadow with a gun.” Other educators said children grabbed safety scissors to defend themselves.

Of the 376 federal, state and local officers who swarmed the campus, only Gonzales and former schools police chief Pete Arredondo have been criminally charged. Arredondo faces similar counts; his trial date is not set.

Jurors must decide whether Gonzales’s actions-or lack thereof-crossed the line from hesitation to criminal negligence. Their verdict will resonate well beyond Uvalde.

Key Takeaways

- First criminal trial over the hesitant Uvalde response.

- 29 counts of child endangerment; maximum sentence two years.

- Prosecutors: officers must act when children cannot defend themselves.

- Defense: conviction risks making police more cautious in future crises.