> At a Glance

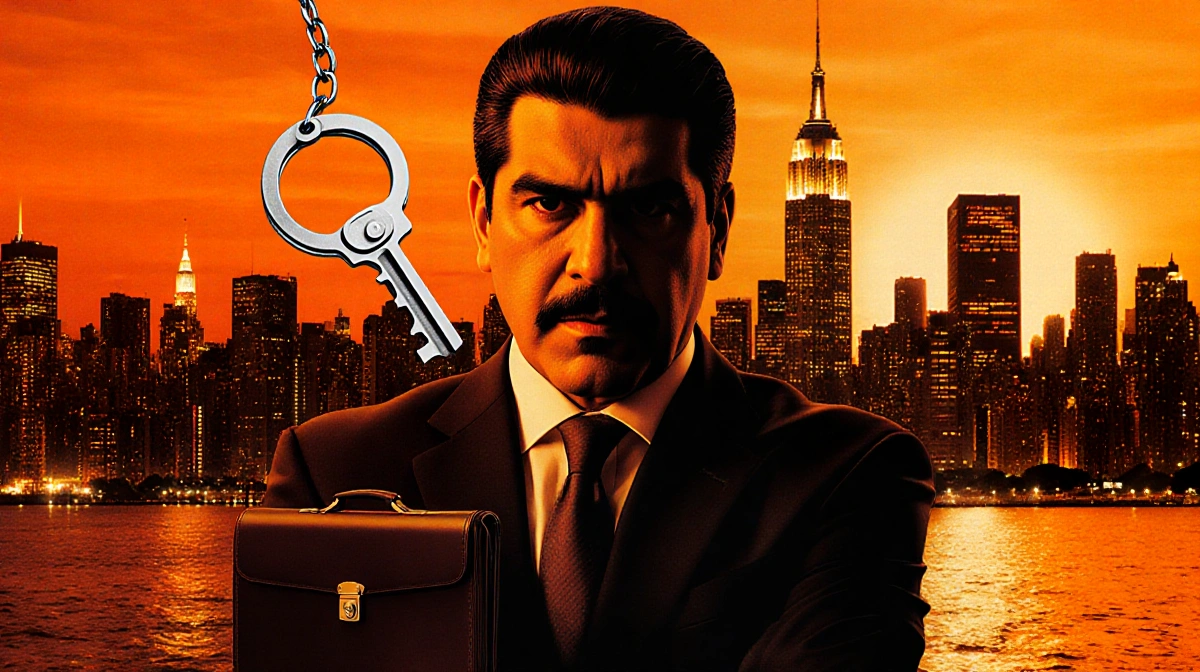

> – Nicolás Maduro appears Monday in New York on U.S. cocaine-importation charges

> – His lawyers will claim sovereign immunity; State Department already labels him a fugitive worth $50 million

> – 1989 Barr memo green-lit forcible overseas abductions, setting precedent for Saturday’s capture

> – Why it matters: The case tests how far U.S. courts will let the executive branch go when it refuses to recognize a foreign leader

Nicolás Maduro’s first court date in Manhattan comes exactly 36 years after U.S. troops snatched Panama’s Manuel Noriega, and prosecutors plan to use the same playbook: deny immunity, proceed to trial, and cite a Justice Department opinion that sanctions forcible abductions abroad.

Immunity Fight Mirrors Noriega Case

Maduro’s defense team will argue he remains Venezuela’s head of state and therefore immune. Several administrations have already rejected that status.

Dick Gregorie, the retired prosecutor who indicted Noriega, said:

> “There’s no claim to sovereign immunity if we don’t recognize him as head of state … Several U.S. administrations, both Republican and Democrat, have called his election fraudulent.”

The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld jurisdiction over defendants brought to the U.S. by irregular means, and the Barr opinion-written months before the 1989 Panama invasion-concluded the U.N. Charter does not bar such operations.

Legal Hurdles Beyond Recognition

David Oscar Markus, a Miami defense lawyer, noted:

> “Before you ever get to guilt or innocence, there are serious questions about whether a U.S. court can proceed at all.”

Key differences from Noriega:

- Noriega never held the title of president

- Maduro claims three electoral mandates, though the 2024 vote is widely disputed

- Governments including China, Russia, and Egypt still recognize him

Despite those points, courts traditionally defer to the State Department, which has offered the $50 million reward and lists Maduro as a fugitive.

Money Troubles for Defense

Years of Treasury sanctions complicate hiring counsel:

- It is illegal for any U.S. person to accept payment from Maduro or his wife, Cilia Flores, without a special license

- Venezuela’s vice-president, Delcy Rodríguez, now running Caracas, faces the same restriction

Indictment Scope

Saturday’s unsealed indictment accuses Maduro and five co-defendants-including Flores and their lawmaker son-of:

- Providing law-enforcement cover for thousands of tons of cocaine

- Supplying logistical support to major traffickers

- Partnering with narco-terrorists to ship drugs into the United States

University of Chicago professor Curtis Bradley expects prosecutors to argue:

> “Running a big narco-trafficking operation … should not count as an official act.”

Policy Backdrop

- First Trump administration closed the U.S. Embassy in Caracas and recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó in 2019

- Biden administration largely retained that stance while engaging Maduro on election talks

- Barr, who oversaw Maduro’s indictment as attorney general, defended the operation on Fox News Sunday:

> “Going after them and dismantling them inherently involves regime change … It’s to clean that place out of this criminal organization.”

Key Takeaways

- U.S. courts are expected to reject immunity because the State Department does not recognize Maduro

- Barr’s 1989 memo and Supreme Court precedent allow prosecution after forcible abduction

- Sanctions make it hard for Maduro to fund a defense team

- Trial will test limits of executive power in foreign policy and criminal law

The stage is set for a courtroom clash that could extend well beyond the initial hearing and shape future U.S. operations against sitting leaders it deems illegitimate.